As refineries shut down across Europe, Africa should be seizing its moment. Instead, the continent is stuck in a crippling loop, building refineries while still importing crude and depending on foreign fuel. It is a self-inflicted vulnerability with a bleak trajectory. By 2050, according to the United Nations, one in four humans will live in Africa. This demographic force will mean little if the downstream sector remains starved of real investment. Without a decisive break from fuel dependence, the future will be precarious. KINGSLEY JEREMIAH reports.

Imagine Africa cut off from fuel imports for just 30 days. Fuel queues will engulf Lagos, Johannesburg, Cairo, Nairobi, Kinshasa and every city on the continent. Aviation will collapse overnight, grounding fleets. Hospitals dependent on diesel generators will face blackouts. Water systems in megacities will lose pressure, waste-collection trucks will stop running, and grid-constrained economies will slide rapidly into disorder. This is not a hypothetical disaster scenario; it is the continent’s structural reality as demonstrated earlier this year by the African Refiners and Distributors Association (ARDA).

Despite producing more than five million barrels of crude oil per day, according to the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), data from ARDA shows that Africa imports over 70 per cent of its refined fuel. The development creates a single point of failure for all major sectors across the continent.

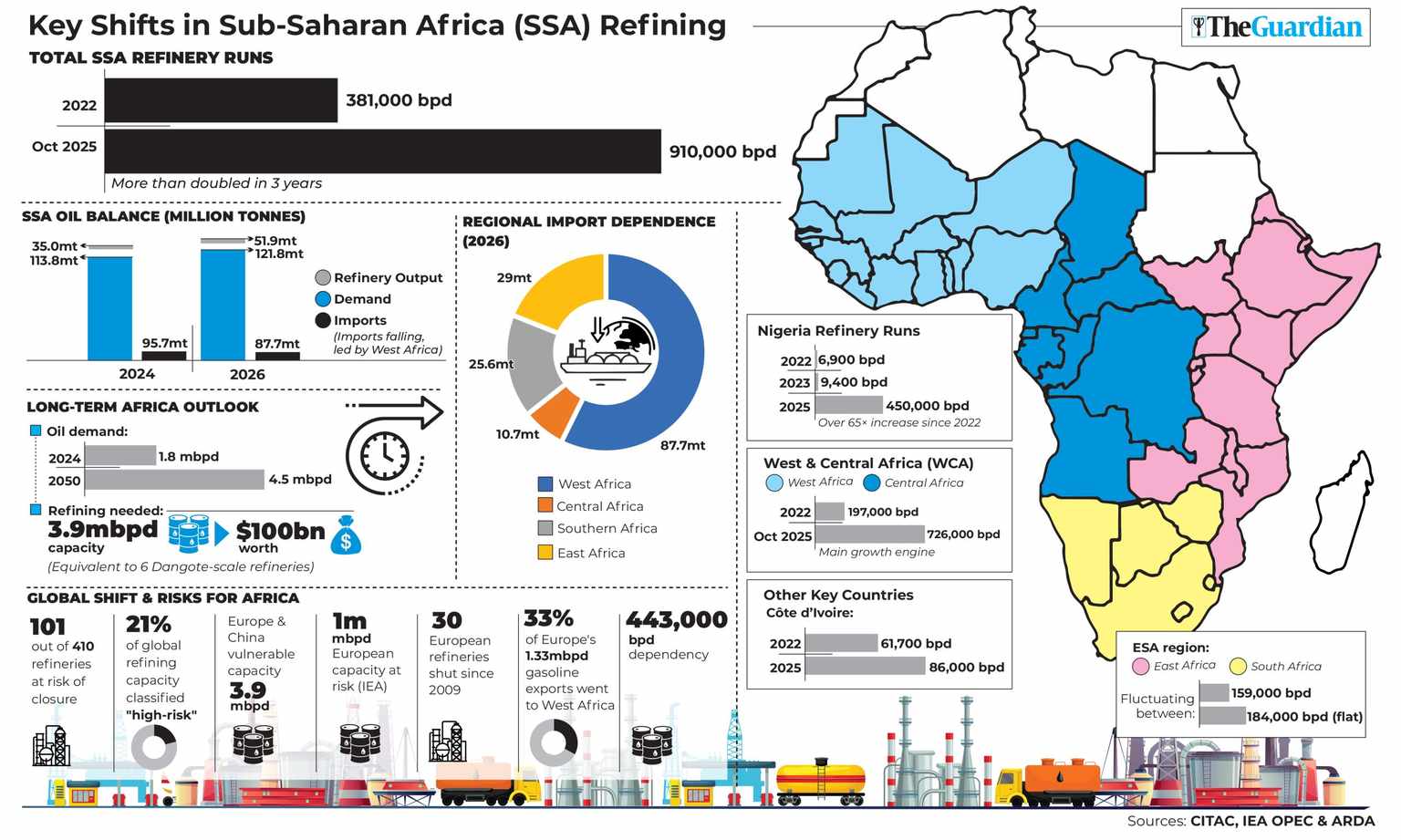

The shifting geography of global refining has worsened the situation. Wood Mackenzie forecasts that 101 out of 410 refineries globally are at risk of closure in the next decade owing to cost pressures, carbon-emission constraints and shifting market economics. Europe, Africa’s largest supplier of premium motor spirit and diesel, is at the centre of this contraction.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), at least one million barrels per day of European refining capacity is currently at risk. A third of Europe’s 1.33 million barrel per day (bdp) gasoline exports in 2023 came to West Africa, predominantly Nigeria, showing the region’s deep reliance on Europe’s shrinking refining base.

Since 2009, nearly 30 European refineries have already shut down, with only about 90 still operating. Some of the refineries, according to data from Argus, are Petroineos (150,000 bpd), Grangemouth (147,000 bpd), BP (257,000 bpd). Others are Eni’s 84,000 bpd Livorno in northern Italy.

Wood Mackenzie’s assessment places 21 per cent of 2023 global capacity in the “high risk of closure” category, with Europe and China holding the largest clusters of vulnerable sites, roughly 3.9 million barrels per day combined.

Africa’s downstream crisis is not merely a domestic failure; it is a collision between internal fragility and external volatility. Without accelerated investment in local refining, storage and distribution systems, the continent remains one global supply shock away from economic paralysis.

Beyond Europe’s shrinking refining base, new global refining capacity over the past three years has gone above 2.5 million bpd, reshaping supply dynamics outside Africa.

The Middle East leads with Saudi Arabia’s 400,000 bpd Jizan, Kuwait’s 615,000 bpd Al-Zour and Oman’s 230,000 bpd Duqm refineries. Mexico’s 340,000 bpd Olmeca and China’s 400,000 bpd Yulong refineries have begun operations.

Constraints Push Nigeria Towards 70 Per cent Importation

IN November 2025, the Nigerian Downstream Midstream Petroleum Regulatory Authority (NMDPRA) downstream snapshot showed a refining sector still far below its potential.

According to NMDPRA, Nigeria has an installed refining capacity of 1.125 million barrels per day on paper across conventional and modular plants, but utilisation remains below 467,000 bpd owing to persistent technical bottlenecks and crude supply constraints.

Between 2000 and 2025, the data showed that Nigeria issued 47 refinery establishment licences outside of existing state-owned 445,000 bpd refineries. However, only four (8.5 per cent) of these investments saw the light of the day in 15 years. NMDPRA disclosed that about three others were actively being built.

The four refineries currently operating are Dangote, Aradel, Edo and Waltersmith with a combined output of 467,000 bpd; while major state-owned plants such as Port Harcourt, Warri and Kaduna, which the Nigerian government has spent about $2.9 billion to revamp, remain dormant.

The regulator revealed that the Dangote Refinery supplied less than half of the petrol it committed to providing for local consumption. The NMDPRA’s State of the Midstream and Downstream Sector Fact Sheet shows that the refinery delivered an average of 18 million litres per day instead of the planned 35 million litres, showing a widening gap between projected self-sufficiency and the reality of persistent import dependence.

If compared with the situation before October 2024, the refinery significantly reduced importation of petroleum products into Nigeria. A critical but often overlooked revelation is that Dangote became Nigeria’s sole source of locally produced petrol throughout the 14-month period captured by the report. NNPC’s four state-owned refineries, despite their combined capacity of over 400,000 barrels per day, did not supply a single litre of PMS. This has created an unintended single-supplier dependence, leaving the entire downstream system vulnerable to the refinery’s fluctuating output, which ranged from as low as three million litres per day to a peak of 25 million.

Compounding this fragility, national PMS consumption surged far more rapidly than government projections. Demand rose from 47.5 million litres per day in October 2024 to 56.7 million litres by October 2025, even with prices above N1,000 per litre.

The upward trend raises fresh questions about cross-border smuggling, economic distortions, and the effectiveness of post-subsidy reforms, suggesting that Nigeria’s demand-management strategy is not working.

The consumption spike translated into massive household spending. Nigerians spent between N1.4 trillion and N2 trillion every month on petrol given the regulator’s data, culminating in N21.8 trillion within 14 months.

This level of expenditure highlights an economy still structurally trapped in petrol dependence, despite official rhetoric encouraging a shift towards gas, electrification, and alternative transport energy sources.

Taken together, the data reveals the contradiction at the heart of Nigeria’s energy policy. Despite commissioning Africa’s largest refinery and investing heavily in state-owned rehabilitation programmes, the country remains reliant on imports, burdened by rising demand and tied to a single domestic supplier.

Rising Energy Demand: Exploring Opportunities in Challenges

THE Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) Oil Market Report released in November by CITAC showed refinery crude runs in the region from 2022 to October 2025 could see a strong rebound driven mainly by Nigeria.

Total SSA runs increased from 381,000 bpd in 2022 to about 910, 000 bpd by October 2025, more than doubling in three years. The most significant shift came in West and Central Africa (WCA), where throughput rose from 197,000 bpd in 2022 to over 726,000 bpd by October 2025.

Nigeria’s refinery runs jumped from 6,900 bpd in 2022 and 9,400 bpd in 2023 to over 450,000 bpd in 2025, according to the report. Côte d’Ivoire showed its rose from 61,700 bpd in 2022 to 86,000 bpd by October 2025. By contrast, Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA) showed limited growth, fluctuating between 159,000 bpd and 184,000 bpd, while Sudan’s output fell to zero.

CITAC’s short-term forecast in Sub-Saharan Africa from 2024 to 2026 (in million metric tonnes) showed that regional demand increased from 113.8 mt in 2024 to 121.8 mt in 2026, driven mainly by West and East Africa. West Africa remains the largest demand centre, led by Nigeria, whose consumption grows steadily despite seasonal fluctuations.

Output increased more sharply, from 35.0 mt in 2024 to 51.9 mt in 2026, reflecting new and expanding capacity, particularly in Nigeria, which accounts for most of West Africa’s output growth. As a result, import requirements decline from 95.7 mt in 2024 to 87.7 mt in 2026, with the steepest reduction in West Africa, where imports fall by over a third.

Central Africa’s demand grew from 13.4 mt to 14.5 mt, while refinery output remained limited, increasing modestly from 4.7 mt to 5.6 mt. As a result, import needs stayed high at around 10.7 mt in 2026, led by Angola and Cameroon.

Southern Africa’s demand rose from 33.2 mt to 35.2 mt, but refinery output largely remained at about 10.8 mt, keeping import requirements elevated at 25.6 mt in 2026, dominated by South Africa and Mozambique.

East Africa’s demand increased from 22.4 mt to 24.2 mt, yet refinery output remained negligible at 0 mt, forcing imports to climb from 25.8 mt in 2024 to 29.0 mt in 2026, with Kenya and Tanzania accounting for most volumes.

On the longer terms, oil demand in Africa is projected to grow from 1.8 million barrels per day in 2024 to 4.5 million barrels per day by 2050, according to OPEC’s World Oil Outlook 2025.

Meeting this surge will require an enormous expansion in processing capacity. ARDA estimates that the continent will need the equivalent of six Dangote-scale refineries. This translates to about 3.9 million bpd refining capacity that would cost roughly $108 billion in capital investment. OPEC’s own forecast aligns with this, projecting over $100 billion in required refining upgrades, expansions, and new projects over the next quarter century.

Yet Africa remains critically constrained in its ability to convert crude into finished fuels. Despite hosting more than 40 refineries, much of its infrastructure is old, inefficient, or chronically underutilised.

In their current state, these refineries post public health concerns by producing petroleum products that are far above specifications, especially the recommended Afric 6 (10ppm) by the African Union Commission.

At the Congo Energy and Investment Forum earlier this year, Minister of Hydrocarbons, Congo, Bruno Jean-Richard Itoua, reiterated the country’s ambition of raising crude output to 500,000 barrels per day, yet the CORAF refinery in Pointe Noire can only process around 21,000 bpd.

The continent’s surging demand threatens to widen this gap further. Africa’s population is expected to reach 2.5 billion by mid-century, accompanied by rapid urbanisation, industrial growth, and escalating transport and power needs.

Without a corresponding expansion in cleaner refining capability, dependence on imported petroleum products will deepen, exposing economies to global price shocks, freight disruptions, and exchange-rate volatility.

The consequences are heavy fuel import bills that weaken currencies, inflated fiscal deficits, diversion of scarce resources from development priorities and persistent foreign exchange outflows that undermine industrial competitiveness, limiting opportunities for value addition, manufacturing expansion, and job creation.

In this context, the refining deficit has become a strategic obstacle to the aspirations of the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Instead of building interconnected regional supply chains, many countries remain tied to refineries outside the continent, reinforcing the very dependencies AfCFTA seeks to break.

Wave Of Refinery Projects In Africa

A wave of refinery construction and rehabilitation across Africa is ushering in one of the continent’s most ambitious attempts to close its long-standing processing gap. Ethiopia, Senegal, Angola, Mozambique, Djibouti, Cameroon, Ghana, South Africa and Uganda are all advancing projects that collectively could add over one million barrels per day of new capacity, an expansion significant enough to not only challenge Nigeria’s dominance, but alter global refining landscape and create energy security for Africa.

Ethiopia is pushing ahead with the 70,000 bpd Gode refinery with China’s GCL, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, said in a statement on X on October 2, this year.

The project is designed to process domestic crude from the Ogaden Basin and reduce its full reliance on imports. Senegal is planning a second national refinery by 2029 to complement SAR, with a budget of $2–5 billion and an explicit goal of achieving fuel self-sufficiency, Chief Executive Officer of SAR, Mamadou Abib Diop, told Reuters on the sidelines of African energy conference in Cape Town.

The Oil and Gas Minister of Angola, Diamantino Azevedo, said the Cabinda refinery is scheduled to start up in 2025 at 30,000 bpd, raising capacity to 60,000 bpd, while the far larger Sonaref project targets 425,000 bpd by 2027, making it one of Africa’s largest emerging processing hubs.

General Manager of the Uganda Refinery Holding Company, Michael Nkambo Mugerwa, disclosed that the country’s $4 billion Hoima refinery is moving into implementation, although commissioning may not be achieved before 2028.

These new projects are emerging alongside recent expansions such as Egypt’s MIDOR upgrade, which boosted its capacity to 160,000 bpd, and Ghana’s 45,000 bpd Tema restart. Together, they represent the most coordinated regional push towards refining independence in decades, driven by fuel import vulnerability, volatile forex markets, and the need for industrial value retention.

In Nigeria, NMDPRA said 47,000 bpd modular refineries are actively being constructed. These are: Waltersmith – Train 2 (5,000), AIPCC – (30,000) and Azikel (12,000). In July this year, Backbone Infrastructure Nigeria Limited (BINL) unveiled plans to build and operate a 500,000 bpd refinery in Nigeria. Already, Sunshine Joint Venture has been formed between Backbone Infrastructure Nigeria Limited, which initiated the project, and NEFEX Holdings Limited of Canada.

Earlier this year, BUA Group issued a release saying its 200,000 bpd crude oil refinery located in Akwa Ibom, South-South Nigeria, was progressing and would be delivered on schedule.

At the same time, several countries are engaged in difficult efforts to revive damaged or mothballed plants. In October, Cameroon’s Prime Minister, Joseph Dion Ngute, said the government would rebuild the National Oil Refining Company (SONARA) in Limbe, which was affected by fire in 2019. The project is expected to be completed in 2027.

In October, Libya restarted Ras Lanuf (220,000 bpd) while there are indications that South Africa is struggling with Engen’s conversion and the prolonged closure of Sapref.

Earlier this year, while speaking at ARDA Week in Cape Town, Director of Development and Energy Transition at Société Ivoirienne de Raffinage refinery (SIR), Raphaël Kouamé Souanga, said the country was building a new 170,000 bpd refinery.

In October, Prime Minister Robert Beugré Mambé said the facility would cost $7 billion.

What is emerging is a continent split between bold new refinery construction and the slow recovery from years of underinvestment. If even half of the announced projects proceed on schedule, Africa’s refining map, spanning North, West, East, and Southern Africa, could be reshaped within a decade, reducing dependence on offshore suppliers and becoming a net importer to other continents.

In May this year, Dangote Refinery exported nearly 100,000 bpd of gasoil, almost double April volumes, with most cargoes heading to neighbouring West African states, according to data from Kpler.

In September, the refinery exported its first shipment of petrol (gasoline) to the United States, carrying 320,000 barrels, which was purchased by global trader, Vitol, from Mocoh Oil on the tanker, Gemini Pearl.

This development is gradually reducing Europe’s gasoil presence in the region. According to Kpler, exports to West Africa fell to a four-year low of 29,000 bpd, while Russian flows dropped to an eight-month low of 87,000 bpd. Strategically, these refineries could help cut the continent’s $17 billion fuel import bill and pressure European refiners that rely heavily on African demand, but the road is still far.

Beyond this, a strong refining sector in Africa will cut import bills for nephtha. IEA said 6.2 million Terajoules of neptha was imported into Africa in 2023 with South Africa (967,650TJ), Nigeria (954,748TJ), Egypt (765,976TJ) and Morocco (570,490 TJ) being the largest. Other sectors like plastic, chemical, engine oil, construction, petrochemical, medical and others will source their imports locally thereby creating security feedstock and strengthening the continents currencies.

High Barriers Despite Opportunities

DOWNSTREAM oil projects across Africa struggle to progress because they fail the basic investor test of bankability and when they find finance they are poorly executed. Global financiers expect predictable feedstock and offtake, stable regulation, enforceable contracts and credible technical and financial models. Instead, they often face inconsistent policies, congested depots, shallow ports, inflation, exchange-rate volatility and mismatched fuel specifications.

While Dangote, for instance, spent over $17 billion in building its refinery, it continues to have challenges over feedstock. Founder of the refinery, Aliko Dangote, said his company’s monthly import of crude oil rose to 10 million barrels from the U.S. and other countries.

Dangote cited the massive technical, commercial, and political hurdles encountered while building his refinery in Lagos, adding that despite the scale of the investment, sourcing crude from Nigerian producers has proved unexpectedly difficult.

“Rather than selling to us directly, international traders bought Nigerian crude and resold it to us at a premium,” Dangote said, while stressing that the refinery was still importing crude monthly from the U.S. and other countries.

According to him, regulatory bottlenecks and prohibitive logistics costs make it more expensive to move crude within the continent than to ship it from as far as India.

“The diesel we refine for Nigeria cannot be sold in Ghana, Togo, or Cameroon. This fragmentation only benefits foreign traders,” Dangote lamented.

Though 46 of Africa’s 54 countries have national standards, the continent, according to ARDA, still uses 12 gasoline grades with sulphur levels from 10 to 2,500 ppm and 11 diesel grades ranging from 10 to 10,000 ppm. Upgrading existing refineries to meet cleaner standards would, according to estimates conducted by the refining association, require about $16 billion.

Infrastructure limitations further undermine confidence as a 2024 CITAC–Puma Energy white paper notes shallow ports, congested berths, inadequate storage and stressed road and pipeline systems, adding $20–30 per tonne to landed fuel costs. Even with new refineries, coordinated investment in transport networks remains essential for energy security.

The crisis between the marketers and refinery owners in Nigeria has also shown that regulatory framework remained weak as well as robust domestic and regional trading of crude and petroleum products.

Stakeholders Proffer Solutions For Bankable Energy Infrastructure In Africa

AFRICA’s slow progress shows the need to confront core questions. How can Africa attract scarce capital, align with ESG standards, and deliver competitive returns?

Managing Director of Premier Invest, René Awambeng, said clear project design, realistic budgeting, and tools like Critical Path Management to streamline execution are necessary. He also called for integration of ESG through carbon tracking and renewable alignment to strengthen long-term viability.

Fidelity Bank’s Emeka Nkemakolam stresses the importance of appropriate technology, optimal plant sizing, reliable feedstock, and risk-mitigating instruments such as turnkey contracts and offtake agreements to cushion inflation and currency volatility. He believes that carbon credits can reduce refinery project costs and unlock green finance.

Managing Director of INDENI Refinery, Zambia, Evans Mauta, canvasses regulatory autonomy to curb adulteration and smuggling, stronger inter-agency coordination, and investment in local energy skills for ethanol, biomass and other alternatives. He urged incentives for low-cost financing, strategic taxation, and greater involvement of pension funds, diaspora capital, and commercial lenders.

The AFC’s 2025 infrastructure report notes that Africa holds over $4 trillion in domestic capital, largely tied up in low-risk assets. AFC President, Samaila Zubairu, advocates for policies that redirect this capital towards long-term infrastructure development like refinery, storage and distribution infrastructure.

Above all, there is a need for Africa to prioritise refineries that produce cleaner fuels through Africa Union’s AFRI-6 low-sulphur standards (10pm), infrastructure that connects the region, full downstream infrastructure upgrades and from ports and storage to pipelines and multimodal logistics. The continent must also promote regulatory stability, disciplined project preparation, turnkey EPC delivery, bankable offtake agreements and ESG-aligned design to attract sustainable, long-term investment.